Dissertation

WILSON, BRADLEY JAMES. The Impact of Media Agenda Setting on Local Governments. (Under the direction of Dr. Dennis Daley).

ABSTRACT: Agenda-setting studies are abundant in mass media literature. Since the early 1970s, the methodology conceived by Don Shaw and Max McCombs has been used to study how media coverage of everything from environmental issues to race relations influences public opinion, mostly at the national level. Subsequently, fewer studies have examined whether agenda-setting concepts can be used to correlate media coverage with policy outcomes, and still fewer studies have been used at the local level. By comparing changes in city budgeted allocations with changes in coverage over time, this study finds a limited, long-term relationship between media coverage and policy changes in four areas: public safety, public works, economic development and parks/recreation. Newspapers have a finite amount of influence over policy changes. Further, this study affirms that while citizens continue to depend on newspapers for local government news, local newspaper circulation, market saturation and staff size continue to decline. Finally, this study shows that by 2011, the Great Recession had begun to strain city and town resources with more impact on the Western region of the United States than other areas.

The Impact of Media Agenda Setting on Local Governments

INTRODUCTION | LITERATURE REVIEW | METHODOLOGY | INITIAL FINDINGS

EXPANDING THE MODEL | CONCLUSIONS | REFERENCES | PDF VERSION

Lane Filler did not set out to start a revolution or to change the direction in which the country is moving when he wrote an article about the city government’s projected shortfall. “Standing in front of a 4-foot-tall wish list for the city of Spartanburg Monday night, City Manager Mark Scott told the City Council he hasn’t figured out how to pay the baseline bills in 2006-2007 (June 13, 2006),†Filler wrote. Maybe not the stuff that spark revolutions, but certainly the meat-and-potatoes reporting that keeps most citizens informed about the actions of their local governments.

Even with such seemingly benign issues, what the citizens learn from the media turns into a desire for action by politicians and, ultimately into policy change, also the focus of this research. “[T]o the extent that the mass media play a role in agenda setting and thus also in problem framing, they are participants in the policy-making process as well as transmitters of news and information†(Milio, 1985). David Nexon, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s (D-MA) health policy specialist, said: “The media senses the public is interested in or unhappy about something and so they write about it. Then the public starts telling pollsters and writing congressmen that there’s a big problem. It takes the media to legitimate an issue as an issue of public concern†(Otten, 1992). Harold Holder and Andrew Treno (1997) showed that increased media coverage focuses public and leader attention on specific issues and approaches to local policies of relevance.

This research examines how the media report on the often seemingly benign issues of local government and how that reporting influences the policy outcomes of local government officials. Specifically, this research, following in the steps of previous agenda-setting research, will determine the correlation between the amount of reporting on local issues with changes in the government budget.

The research builds on familiar concepts. For example, as Allen Otten, a veteran reporter for the Washington bureau of The Wall Street Journal, said, policymakers often encounter their first information about a problem or its urgency from the press even if the media outlets were conveying the problem from an advocacy group, from a research organization or from the general public. “Every agency or congressional staffer knows how often the boss starts the day demanding to know more about an item in that morning’s paper or on the previous night’s news. The press puts the information into the policy-making process.†Jack McLeod (1999) found that individuals partaking of institutional activities read hard, local news and became more knowledgeable about local politics as a result. Their knowledge, in turn, gives the local political system a higher level of efficacy. Politicians and administrators alike use the media to improve the efficiency of their agencies and to show that they are responsive to the concerns of the citizens.

Because the media can focus attention on an issue as well as on its solutions, public administrators and politicians need to know what role the media play in setting the agenda. The political consequences of the media’s priorities can be enormous. Policymakers may never notice, may chose to ignore or may postpone indefinitely considerations of problems that have little standing among the public. Still, more than 80 percent of legislators and almost 90 percent of interest groups said the media were important at the local level to communicate organizational views (Lee, 2001). But the ability to increase the salience of an issue with the public is but the beginning of the story. For reporting to be useful to politicians and to reporters the salience of the issue must translate into policy change. News attention alone is insufficient without specific policy goals and community organization to support these goals.

Certainly, there are examples of when reporting, often combined with external factors, has resulted in policy change. Holder and Treno (1997) studied the national problem of driving under the influence of alcohol and showed that such reporting was more effective than a paid public information campaign. Other researchers have studied everything from the relationship between media coverage and the Vietnam War to safety on the nation’s highways to the national War on Drugs. While national issues make headlines every day, comparatively little research has been done about what impact local media can have on policy, the specific focus of this research. Ithiel de Sola Pool (in Schramm, 1963) argues that media outlets would be more effective if they covered more local contests so they could mobilize the more sluggish but basically more persuasive oral communication system. “The press pays great attention to a presidential campaign. It gives thousands of columns of space to it. Yet the net effect of the press on the voter’s choice is small. It gives very little attention to contests for minor local offices. Yet its net effect on the voter’s choice for these is substantially greater.†He summarizes, “The press in the United States is much more influential in local than in national elections.†With those ideas in mind, this research examines the agenda-setting role of the local media on policy outcomes.

In addition, it is important to discuss why, when media outlets themselves are reporting on their own demise[1], this research revolves around the print media. While daily, largely regional and national newspapers have seen a significant decline in circulation, smaller towns and cities without the benefits of numerous television stations or regional media still find value in their local newspaper. “CNN is not coming to my town to cover the news, and there aren’t a whole lot of bloggers here either,†said Robert M. Williams Jr., editor and publisher of The Blackshear Times in Georgia. “Community newspapers are still a great investment because we provide something you can’t get anywhere else†(Liedtke, 2009). Local newspapers, and local issues, do not draw the attention of the larger newspapers, television stations, the Huffington Post or Jon Stewart. “We still think community newspapers have an audience and it’s not going away,†Richard Connor, publisher of The Times Leader in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., (weekday circulation of about 36,000), said. “There will always be an audience for local news†(Liedtke, 2009).

Further, smaller newspapers avoided some of the staff cuts made by the rest of the industry, which, by late 2009, had eliminated more than 100,000 jobs since 2005. An Inland Press Association study found daily newspapers with circulations of less than 50,000 were spending more on their newsrooms in 2008 than they were in 2004. While ad revenue dropped 4 percent at more than 1,000 community newspapers responding to a survey by the National Newspaper Association and the Suburban Newspapers of America, industry-wide, national newspaper ad revenue plunged 17 percent (Liedtke, 2009). Although local newspapers were not immune to industry trends, they seemed to decline at a slower rate. Local newspapers are stable, cover a specific community and are likely to cover fiscal issues in that community, making them the ideal candidates for research. “If it walks, talks or spits on the concrete in our area, we cover it,†said John D. Montgomery Jr., editor and publisher of the weekly The Purcell Register in Oklahoma, based about 40 minutes south of Oklahoma City with a circulation of about 5,000 by focusing on Purcell and four nearby towns with a combined population of about 17,000 (Liedtke, 2009). Indeed, as David Simon, a reporter for the Baltimore Sun for 13 years and former executive producer of HBO’s “The Wire†(a drama that concluded in early 2008), said in his 2009 commentary, “A good newspaper covers its city and acquires not just the quantitative account of a day’s events but the qualitative truth and meaning behind those events. A great newspaper does this routinely on a multitude of issues, across its entire region.†It is those newspapers that will be the focus of this study.

Theoretical Foundation

Agenda-setting research started in communication research. It has since taken root in many other disciplines, including political science, public administration, public policy, sociology, psychology and social psychology. Contemporary agenda-setting research, including this study, synthesizes ideas based largely on communication about decisions in agenda setting and draws on theories within public administration, such as the institutional theory Garbage Can Model of Michael Cohen, James March and Johan Olsen (1972) and the public-sector evolution of that model by John Kingdon (2003) in the development of his Multiple Streams Framework.

The models begin with the concept of the garbage can of ideas conceptualized by Cohen, March and Olsen, who believe the garbage represents the ideas generated as the various solutions for any problem. “The mix of garbage in a single can depends on the mix of cans available, on the labels attached to the alternative cans and on what garbage is being produced, and on the speed with which garbage is collected and removed from the scene.†Similarly, while looking at nuclear power, tobacco use and pesticides, Baumgartner and Jones (1993) discussed how waves of enthusiasm sweep through the political system as political actors become convinced of the value of some new policy and how the mobilization of the apathetic provides the key to linking the partial equilibria of policy subsystems in American politics to the broader forces of governance. Both sets of researchers acknowledged that the media play a role in this mobilization and, ultimately, in policy change. But it was Kingdon (2003) who integrated the ideas into a Multiple Streams Framework. He said that at any given time, government officials and people outside of government closely associated with those officials may pay attention only to a limited list of subjects or problems —their agenda. The solutions to the problems on the agenda came from a set of alternatives seriously considered by governmental officials and those closely associated with them. Kingdon conceived of three streams of processes: problems, policies and politics — each with lives of their own. People recognize problems; they generate proposals for public policy changes; and they engage in political activities. Alternatives are generated and narrowed in the policy stream. When the three streams join, a pressing problem demands attention for a specific instance. Solutions are possible in a decision agenda, pushed there by policy entrepreneurs.

The media can play a significant role at any significant point in his process by identifying a problem initially, by identifying multiple solutions such as those in the garbage can of ideas and by motivating policy entrepreneurs to push for a specific solution. Kingdon said the media, one of the vehicles for policy change, are important because (1) they are communicators within policy community; (2) they can magnifying movements that have already started elsewhere; (3) to the extent that public opinion affects some of the participants, they might have an indirect effect.

It is this third aspect, the impact of the media on public opinion, which most research regarding media agenda setting examines. That the media can influence public opinion has been clearly established through agenda-setting studies. Max McCombs and Donald Shaw, who wrote “The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media†in 1972, showed that, at least when it comes to national issues, by ignoring some problems and attending to others, the mass media profoundly affect which problems readers, viewers and listeners take seriously. Problems prominently positioned inevitably loom large in the minds of potential voters. Case studies, content analyses, quasi-experiments and other studies have shown that, at least to some degree, news coverage is a significant predictor of shifts in public opinion (Funkhouser, 1973; McCombs and Shaw, 1993; Page and Shapiro, 1992; Weaver, McCombs and Spellman, 1975).

In addition to the theoretical relevance, the research also derives from political science in the application of work done in public opinion, particularly the use of public opinion polls. As Benjamin Page and Robert Shapiro (1983) said in “Effects of Public Opinion on Policy,†the responsiveness of governmental policy to public opinion is a central concern and there is no shortage of theories regarding the extent to which policy does or does not respond to public opinion. “[O]pinion changes are important causes of policy change. When Americans’ policy preferences shift, it is likely that congruent changes in policy will follow.â€

The importance of public opinion should not be underestimated. As Bryan Jones and Frank Baumgartner (2004) have shown, there is an “impressive congruence†between the priorities of the public (as indicated by public opinion polls) and the priorities of Congress as well as lawmaking activities across time. As shown in the literature review (in chapter 2), the research concedes the impact of the media on public opinion and, unlike much other research, moves beyond public opinion to examine policy outcomes.

The vast majority of this research, including the McCombs and Shaw study, made use of the answer to the question: “What do you think is the most important problem facing this country today?†(Smith, 1980). Little, if any, data with the answer to that question at the local level exists making it impossible to replicate national research regarding the correlation between public opinion and media coverage at the local level.

Local Media and Policy Outcomes

Perhaps the most important reason for skepticism regarding the importance of the media in agenda setting at the local level is that voters are already likely to be engaged in the activities of their local communities, and therefore more informed on issues of local importance. While a debate on terrorism, unemployment, the trade deficit or inflation undoubtedly will incite a lively discussion nationally, the impact that a single individual can have during the discussion is minimal. However, propose an increase in property taxes or fail to plan for traffic and not only will the outcry be loud, although often from a few people, but also the individuals involved are more likely to impact change. “Many national political issues may be perceived by individuals to have little direct impact on their personal affairs. … A local plan for the busing of students, however, may inspire vigorous personal concern and participation in the political process†(Palmgreen and Clarke, 1977).

John Schweitzer and Billy Smith (1991) set out to determine which had more impact on the selection of a site for a nuclear waste-dump site in extreme West Texas. Although limited to one controversial issue, the cities included were isolated and received little coverage from large, metropolitan media so the impact of the local newspapers could be examined. They found that in small communities the public tends to set the agenda for media coverage. “[C]ommunity newspapers in the middle of a local controversy are subject to many more pressures to report from the point of view of the community rather than from some professional standard of ‘objectivity,’†Schweitzer and Smith wrote. “Larger newspapers, located in communities of greater pluralism or more removed from the heat of the controversy, are freer from pressure and thus may practice the ideas of objective journalism.†In this case, pressure from local citizens and local media was among the factors that ultimately led to the selection of a dump in another location. The research typifies the significant body of literature that shows that local, community newspapers are different from newspapers in larger communities. Small newspapers act as the voice for community consensus and metropolitan newspapers act as the voice for community dissent (K. Smith, 1984).

How the local media cover those issues can also impact how readers perceive those issues. Researchers have applied agenda-setting theories to show that mass media not only play a key role in informing the citizenry about local issues (Chaffee and Frank, 1996) but also, by covering certain issues more prominently, the media increase the salience of those issues among citizens. In their research about the development of a controversial commercial development in Ithaca, New York, Sei-Hill Kim, Dielram A. Scheufele and James Shanahan showed that by covering specific decisions about an issue prominently, the mass media influenced how salient the issue was among citizens. “The media play a key role in indirectly shaping public opinions for a wide variety of issues on a day-to-day basis, especially in small communities with a limited number of media outlets for citizens to choose from.â€

While media outlets may play a key role in shaping opinion, the role newspapers play at the local level is less certain. McCombs (2006, e-mail) notes, “There is very little work in the entire field of political communication on state and local elections and public opinion.†While not plentiful, some of the work in agenda setting at the local level, where this research has its focus, is revealing. For example, researchers have shown that a newspaper in Florida was pivotal in encouraging more public input into the process of developing a public safety building (Simmons, 1999) and that the media can have an impact on perceptions about unemployment under certain conditions (Soroka, 2002). A newspaper in Texas brought to light — and forced change in policy issues regarding children — everything from poverty to healthcare to education (Brewer and McCombs, 1996). And newspapers clearly have an edge on other forms of media at the local level. Comparison between newspapers and television in Ohio showed that newspapers were the dominant agenda-setter at the local level (Palmgreen and Clarke, 1977).

Using the past research at the national level as a foundation, this research focuses primarily on what matters the most — change in policy — in the public administration arena. While it is impossible to ignore the influence of public opinion and the political environment, they are but intermediary steps in a logical progression leading to policy change. In addition, research has shown that the impact of the media will decrease as people become more informed about the issues and, therefore, depend on the media less. At the local level, it also seems plausible that the media will serve less as agenda setters because other methods of communication, such as word of mouth, play a greater role in informing the decision-makers. All of these factors play a role in any examination of the agenda-setting role of newspapers on public policy at the local level.

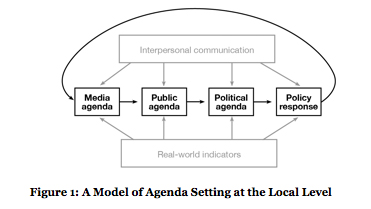

To that end, figure 1 represents a model of agenda setting used in this research, a model representing key advancements beyond previous models. Based originally on a model by Everett Rogers and James Dearing (1988), figure 1 maintains their concept that interpersonal communication and real-word indicators can have an influence upon the agenda at any level and to varying degrees. Media outlets do not operate in a vacuum. Nor do media outlets operate in a statistically valid, unidirectional world where information would flow only in one direction.

Yet this is not the only model. Using a their own model (figure 2) that looked at one piece of the bigger model, researchers Thomas Johnson, Wayne Wanta and Timothy Boudreau (2004) showed how newspapers increased reporting on drug use as drug use in America increased. In turn, in a flow that illustrates use of the model, presidents devoted more attention to drug use in their presidential statements as part of the political agenda. They did not study whether policy changes were made following media coverage and real-world indicators. Their Path Analysis Model of Agenda Building not only focuses on real-world cues but also illustrates how media coverage can both lead to public approval and result from public approval of the real-world cues. Because of this feedback any reasonable model must include a feedback loop as in figure 1, a diagram that also makes it easier to understand why correlation is a useful statistical method because the correlation acknowledges that the amount of influence can be bi-directional (Campbell and Stanley, 1963; Ellett and Ericson, 1986).

The model used for this research (figure 1) also maintains the linear relationship between the varying agendas, which are loosely comparable to the streams mentioned in John Kingdon’s model. The diagram adds the political element, which clearly is an influential factor in getting policies or laws changed.

Finally, the model in figure 1 adds a definitive feedback loop between the policy response and media agenda, a loop at which other researchers have speculated but rarely articulated. To show that the model is indeed complex and employs a variety of feedback mechanisms, Johnson, et. al. (2004) determined that the path from presidential statements to subsequent media coverage was as strong as the one from media coverage to subsequent presidential statements. Also, Kim Smith (1984) noted that the media are likely both to affect and to be affected by public opinion.

Research Statement

Does agenda setting work at the local level? Or, phrased differently, can the media influence policy outcomes at the local level? These are not questions without any exploration in the literature surrounding agenda setting, but they are questions without substantive examination in the history of politics-journalism interaction. Acknowledging that causation cannot be inferred by correlation, the exploration of the answers to these questions is a logical extension of the work done at the national level and provides insights into the factors that influence the passage of law and policy at the local level. Because it is not clear whether local-level agenda setting works or works in the same way, this research looks specifically at the impact of the media on policy outcomes. While paying less attention to the intervening public and political agendas, it concentrates on what aspects of the media seem to be the greatest predictors of policy change.

- H1: Local coverage and policy change will be positively correlated. The coverage of the local newspaper will have a positive correlation with the change in the budget of that same item to show that the items are related.

- H2: The size of a newspaper’s staff will correlate positively with policy change. The larger the size of the staff, the larger the positive correlation. After showing through review in the literature that staff size influences the depth of local coverage a paper can generate, this research will examine how staff size is related to changes in the community budgets.

- H3: The higher the quality of the newspaper as measured through market saturation, the higher the correlation between local coverage and policy change. The greater the market saturation of a paper, the more chances it has to influence public opinion and the opinion of town leaders, ultimately influencing policy change.

- H4: Local newspapers with a Web presence will show a higher correlation between local coverage and policy change. Another form of market saturation for a newspaper in the age of news media is the online edition. The more the paper is viewed, online or in print (as determined by market saturation in H3), the more chances it has to influence public opinion and the opinion of town leaders, ultimately influencing policy change.

- H5a: Locally owned newspapers will have a stronger correlation between amount of coverage of local issues and policy change than newspapers owned by national chains. Local newspaper publishers and editors themselves become leaders in the community and have a vested interested interest in covering issues that result in positive change in their community.

- H5b: Local newspapers owned by the same company as the local television station will show a higher correlation between local coverage and policy change. When media work together, they tend to use the same material so the cooperation results in increased saturation of the story. Like coverage on the Web and newspapers that are locally owned, increased coverage of the same story on local television will result in policy change.

Each of these hypotheses, using information reviewed in chapter 2, are tested through examination of local newspapers and local governments. The next chapter examines other literature that serves as the foundation for this research, generally research at the national level. Chapter 2 also contains an in-depth analysis of research on agenda-setting at the local level and criticisms of the agenda-setting theory. Building on the material in chapter 2, chapter 3 continues with a methodology for this study of the policy outcomes in local government influenced by local newspapers. With the road map drawn out and implemented in the first three chapters, chapter 4 includes an initial discussion of the findings and basic correlations. Chapter 5 elaborates on those findings with a more in-depth analysis. Chapter 6 concludes with various notations of problems found along the way and limitations of the research, a discussion of the implications for application of this research in public administration and mass media as well as a discussion of potential future research.

[1] A Google search of “demise of newspapers†(one of the top search phrases) returned more than 1.5 million hits in late 2009 and 8.27 million in April of 2011. Of those in 2011, 74,800 matched the phrase exactly.

INTRODUCTION | LITERATURE REVIEW | METHODOLOGY | INITIAL FINDINGS

EXPANDING THE MODEL | CONCLUSIONS | REFERENCES | PDF VERSION