Initial Findings

INTRODUCTION | LITERATURE REVIEW | METHODOLOGY | INITIAL FINDINGS

EXPANDING THE MODEL | CONCLUSIONS | REFERENCES | PDF VERSION

Â

In the early 1970s, researchers examining national issues showed that by ignoring some problems and attending to others the mass media profoundly affect which problems readers, viewers and listeners take seriously. Since then, more than 400 case studies, content analyses, quasi-experiments and other studies have shown that news coverage is a significant predictor of shifts in public opinion (Funkhouser, 1973; McCombs and Shaw, 1993; Page and Shapiro, 1992; Weaver, McCombs and Spellman, 1975). The vast majority of the qualitative work, including the pivotal work by McCombs and Shaw and subsequent studies, involved the use of correlations to determine if there was a relationship between media coverage and public opinion. In that sense, this research is no different, using correlation as the primary method of statistical analysis. The results in this chapter, primarily, reveal those relationships.

Further, this chapter expands the research beyond public opinion, examining the relationship between media coverage and policy outcomes, just as researchers such as Robert Spitzer (1993) did when they discussed how media outlets play a pivotal role in influencing policy because they regulate the flow of communication between policymakers and others in the political system. Case study after case study showed how, in specific, highly publicized and controversial decisions, the media can impact policy outcomes. Expanding on this work, in a quantitative, longitudinal study, Peter Mortensen and Søren Serritzlew (2006) concluded that the media may affect political discussions and certain political decisions, but the budgets and broader policy priorities remain largely unaffected. Their quantitative study used yearly net operating expenditures during 13 years in 191 municipalities to examine whether media pressure had an impact on budgetary decisions. “Almost no observable effects of media pressure are found, either generally or in favorable political, economic or institutional settings.†However, most of the previous research was either overseas, involved isolated instances or large, regional media outlets. There remains little research on local newspapers and their impact on policy outcomes. So, this chapter reveals the relationship between budgets of local governments in the United States and coverage in the community newspapers in the EBSCO Newspaper Source Pro database. The findings reveal little relationship between newspaper coverage in the short-term and only a relatively small relationship over the longer term. While newspaper coverage might indeed influence public opinion, it seems to do little to influence the ultimate opinions of policy makers. Even when results were significant statistically, effect sizes were small.

Finally, this chapter examines the other variables used in the study including ownership, online presence and staff size.

Descriptive Data

Before jumping into the details of the relationship between the towns, their policy outcomes and media coverage, it is useful to have a picture of the towns and media studied including population and circulation characteristics that led to market saturation statistics. The descriptive statistics shed some light on the characteristics of the towns and their newspapers (appendices a, b and c).

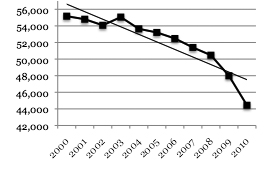

The local newspapers had an average circulation of 44,437 in 2010, down from close to 55,000 10 years earlier, a decline of nearly 19 percent in less than decade (figure 5) and a decline of 13 percent between 2000 and 2009. This was similar to circulation data from the Newspaper Association of America that showed a decline of 17 percent from 2000 until 2009, the latest year for which comparable, comprehensive data was available (Newspaper Association of America, 2011). Data from the Audit Bureau of Circulation showed a 5 percent decline in the first months of 2010 and 10.6 percent in 2009 (Peters, 2010). The NAA data showed a strong correlation (r=0.97**) with the newspapers in the sample group, but it is possible that the papers in the sample were part of the NAA data set. Larger papers, the top half in the study, saw a decrease in circulation of 18 percent over the decade while smaller papers, the bottom half in the study, saw a decrease of 24 percent. As newspapers reach fewer and fewer people, the potential impact on public opinion and policy outcomes declines. Because it circulation declines are exaggerated in the smaller communities, reaching up to a decline of one-fourth of market share, lack of coverage might mean that media outlets have even less of an impact in smaller communities.

Figure 5: Average Circulation of Newspapers Used in this Study

over the Last Decade.

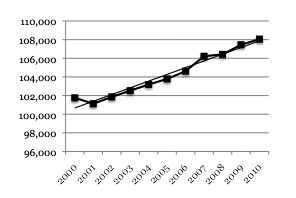

In contrast to the circulation declines, the towns, in 2010, had an average population of 108,052 that increased at a rate of about 6.2 percent over the decade (figure 6). This was roughly comparable to a 9.7 percent increase nationally between the national census in 2000 and the 2010 census. The 2010 Census reported 308.7 million people in the United States, a 9.7 percent increase from the Census 2000 population of 281.4 million with the largest growth (14.3 percent) occurring in the South (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Figure 6: Average Population of Towns Used in this Study

over the Last Decade. Provided by the U.S. Census Bureau.

As expected, the population of the town was strongly correlated to the circulation of the newspaper (r=0.67**). The larger the town, the higher the circulation of the newspaper. Population explained about 45 percent of the variance in circulation and that relationship was highly significant. That strong correlation and high significance helps to validate the use of market share as a combination of both population and circulation in the final analysis. Similarly, papers with larger circulations required larger staffs. This relationship was also strong (r=0.70**) and highly significant. The circulation explained 49 percent of the variance in staff size. Decline in circulation can certainly explain part of the decrease in staff size over the past decade, but part of it can also be attributed, intuitively, to improvements in technology that require fewer people to produce the same number of pages and the changes in ownership that demand higher profit margins. Similarly, local ownership seems to explain about 2 percent of the variance in circulation (r=0.18*).

The Budget

The first relevant finding related to the budgets of the cities and towns in this study was the relative inaccessibility of the budgets themselves despite increased use of websites and online media to distribute financial information. No source compiles the disaggregated budgets of local governments. The U.S. Census Bureau provides online links to many of the cities, towns, counties and other forms of the 89,527 governments (everything from cities to school districts). The inaccessibility of such data is perhaps one primary work for scarcity of work in local budgeting. Hence, each local government included in this research had to provide their budget for the last several years (usually available to anyone through online resources). From the budgets the individual items had to be pulled and compared with previous years. The aggregate budget was not useful because the total allocation for a municipality has more to do with population growth than any policy change. As McCombs (2004) says, “[T]he strength of agenda-setting effects can vary from issue to issue.†He adds, “The intense competition among issues for a place on the agenda is the most important aspect of this process. At any moment there are dozens of issues competing for public attention. But no society and its institutions can attend to more than a few issues at a time. The resource of attention in the news media, among the public, and in our various public institutions is a very scarce one.â€

While most towns made their budgets accessible either online or by e-mail, another challenge in obtaining the information was government officials themselves. Some, like the director of finance for Willoughby, Ohio, would not release the town’s budget without an expensive and time-consuming public records request. While that town publishes the Certified Annual Financial Report as mandated by the state government online, it did not publish an of its budget information online in advance of the council’s approval or even after approval. And, in Indiana, the clerk/treasurer of Seymour reports that “the actual budgets never get published.†He said, “…[W]e are required to advertise a document that shows the potential changes in the amount of tax levies for each fund. To the average citizen, I’m sure this is totally non-informative.†He also said the local newspaper might report on potential changes in the tax levy, since that is the information provided by the town, the paper does not report on the budget. Indeed, he said his town is “blessed†by the lack of interest in the town’s budget or budget process (Lewis, 2011). Both of these cities were removed from the pool of cities studied because the budget information was ultimately unobtainable.

Nevertheless, as Mortensen and Serritzlew (2006) indicated, the public budgets provide a condensed measure of policy and, indeed, the only generally accessible vehicle for such a study. With the budgets over several years from nearly 150 towns in hand, the first anecdotal finding that became apparent was that towns were worried about meeting their financial obligations. A report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (McNichol and Johnson, 2010) found, “The worst recession since the 1930s has caused the steepest decline in state tax receipts on record.… When all is said and done, states will have dealt with a total budget shortfall of some $375 billion for 2010 and 2011.… The federal assistance to states provided in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is lessening the extent to which states need to reduce services or raise taxes. But it now appears likely the federal assistance will end before state budget gaps have abated.â€

A report issued by the National League of Cities and Brookings Institution in 2009 found that “Nearly nine in 10 city finance officers … report difficulties meeting fiscal needs in 2009. In aggregate, these cities face nearly 3 percent budget shortfalls on average this year. And the sense of trepidation is ubiquitous across a diverse range of metros, regardless of which aspect of the national crisis impacts them the most: declining consumption rates and increased property foreclosures; job losses in manufacturing or financial services; or record state budget shortfalls. Yet this is only the beginning of what will likely be a slow-moving crisis. …[C]ities and other localities will be contending with increasing budget pressure for the next several years.†A Brookings Institution report of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in America revealed similar findings (Wial, et. al., 2011).

However, despite all the discussion of the Great Recession that began in December of 2007 and officially ended in June of 2009, the towns in this budget were not yet showing significant budgetary declines although they were seeing a decline in revenue. Further, some cities in this study had clearly been hit harder than others. Marysville, Calif., for example, led its website with an article about why officials were turning off half of the street lights due to budget constraints. That city (population 12,072) had a budget decline of 17 percent between 2007 and 2012. Even towns the size of Chattanooga, Tennessee (pop: 167,674) saw significant budget declines in a similar time period, from $278,417,355 in 2005 to $167,535,000 in 2010. As Cliff Hightower reported in his article on budget cuts in the Chattanooga Times Free Press (Aug. 22, 2011), “Staring at a $13 million shortfall this year, Hamilton County chose to cut millions of dollars from its budget, laying off 36 workers, freezing 20 jobs and ending some services. Just 12 months earlier, Chattanooga looked at its own potential shortfall and raised property taxes by 37 cents.…†In the article, Hightower quoted County Mayor Jim Coppinger: “This was a really tough budget because of the reductions. These are real people, and all of us were very sensitive to what was occurring.†Even Dover, Del., a city that was experiencing steady budget growth (up 62 percent in the five-year period of 2005-2010), has seen significant (10 percent) declines in the last two years. As Craig Anderson and Chris Flood reported in the Delaware State News (2011), “With the next fiscal year budget predicted to be $3.4 million short, Dover City Council members have been tasked with some difficult decisions. Topping that list is deciding which of the 23 vacant city positions need to be filled and which ones don’t.†And an earlier article had the simple headline: “Dover committee looks for ways to cut budget†(Eisenbrey, 2011). Clearly budget cuts were on the minds of city officials and reporters.

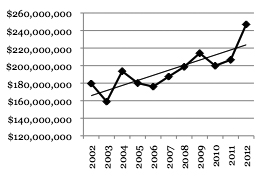

Despite the talk of budget cuts, talks that seem to have grown more prominent since 2008, in the five-year period between 2005 and 2010, one of the five-year periods used in this study, the cities used saw an average of 3 percent growth (range: -40 percent to +60 percent), slightly smaller than the population growth of just under 4 percent. Anecdotally, local governments, governments that have seen a steady increase in population, decrease in local tax revenues and decrease in federal disbursements, believe the budgetary impact is just now hitting them and that budget growth is not keeping up with population growth (figure 7). The recession does not seem to have hit the average town used in this study. However, the effects could be delayed as decreased allocations from federal and state governments may not yet be impacting town governments, the governments may be using reserves built up in the boom years to compensate for decreased revenue, or towns may have increased taxes and fees to compensate even over the short term. This study examines only the expense side of the budget, not coverage of local government income or how income has changed during the early part of the century.

Figure 7: Average Budget of Towns Used in this Study over the Last Decade.

The Relationship

The most important part of this research, however, did not involve looking at what was already painfully obvious in terms of population growth or circulation decline. It involved looking at the relationship between newspaper coverage and policy outcomes. Similar to the research done by Meagan Jordan (2003), this research examined the line items of 143 towns and their newspapers in four areas: public safety, public works, economic development and parks, recreation and tourism to determine if the media might be more influential in any one are over another. It is worth noting that the study of 143 towns represents the analysis of 143 town budgets (each with hundreds of lines that had to be aggregated into the areas of interest), and 52,195 daily newspapers per year, about 808,679 terms in 2010 alone. The percentage difference in the terms was correlated with the following year’s percentage difference in the budget hypothesizing that budget changes followed newspaper reporting.

| Table 7: Newspaper Terms Correlated with Town Budget | ||||

| Â | 2008-2009 Correlation (r) | 2009-2010 Correlation (r) | 2010-2011 Correlation (r) | 2011-2012Correlation (r) |

| Economic development | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Parks, recreation and tourism | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.39*** |

| Public safety | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.38*** |

| Public works | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.15* | 0.21** |

| Total terms | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| Â | n=135 | n=137 | n=133 | n=118 |

|

*Correlation is significant at the 0.10 level (2-tailed) |

||||

The same methodology used in so many studies beginning with the original agenda-setting studies and now so prevalent in the literature, simple correlation, was used to establish whether there was a relationship or not. In the four years analyzed, (table 7) there were few significant instances where media coverage had an impact on budget outcomes, coinciding with Mortensen and Serritzlew (2006) who also found media coverage had small significant effects on coverage of public libraries (r= 0.00) and child-care provision (r= -0.01) but not public roads or primary schools. Even when the findings were significant, the effect sizes were small, explaining 15 percent of the variance in policy change at most. Jacob Cohen in his 1988 book on statistical analysis would say the correlations found in this one-year portion of the study ranged from insubstantial (r=0 to 0.1) to small (r=0.1 to 0.3) to moderate (r=0.3 to 0.5). None of the findings indicated large correlations (r>0.5). In short, this seems to indicate that coverage in a community newspaper has little relation to policy change over the short-term.

Public safety: Public safety occupied the greatest portion of the town budgets and increased by 3.4 percent over the three-year period from 2008-2011 and proportionally during each individual year. Even if towns devoted all of their average increase to public safety, they would still have to move another 0.7 percent of their budget into public safety to account for the change in allocations. Perhaps devoting more than one-fourth of the town budget is a reflecting of living in a post-9/11 world or perhaps is merely a reflection that public safety (police, fire and EMS) is a task best relegated to the local governments that have direct contact with their citizens, and the ability to tax them for their efforts. As significant as public safety was in the budget, it was also significant in coverage of everything from wrecks to house fires to crime and personnel changes at the highest levels of public safety within local governments. Yet this coverage showed significance in only one year, 2011-2012 at a moderate level (r=0.38). It also showed increased correlation (from r=0.04 in 2009-2010 to r=0.14 in 2010-2011 to r=0.38 in 2011-2012). There is no obvious explanation for this increased relationship.

Public works: Public works budgets changed the least (+0.05 percent), seemingly indicating that towns had little flexibility in cutting (or increasing) town budget allocations for infrastructure such as road maintenance, sewage treatment and water purification. In some ways, public works is the one aspect of the budget studies that hits every citizen every day. While citizens generally interact with public safety officials during a crisis, only take advantage of parks, recreation and tourism efforts as needed and rarely notice economic development efforts (including taxation), they quickly notice pot holes in the roads, a lack of water availability or inaccessible sewage treatment. So, that public works was at least weakly correlated in two of the years studied indicates that as media coverage influenced public opinion, policy change resulted in terms of budget allocations. This was not surprising. When aspects of public works are functioning, people hardly notice. But when something breaks, they notice and so do media outlets as stories with headlines such as “Water, Sewer Treatment Plants In Bedford, Franklin Counties Fined†(Hammack, 2010), “Roads Need Our Attention†(Greeley Tribune, 2009) and “Garbage Collection Suspended†(Mangione, 2005) indicate. Still, there is no obvious explanation for why the correlation jumped from r=0.00 in 2009-2010 to r=0.15 in 2010-2011 and increased again marginally in 2011-2012 to r=0.21, but all the increases were similar to those found in public safety. Over time, public works is also unique in that costs for maintenance, construction and upgrades, can be deferred for a short time period. While media coverage pressures may push politicians and bureaucrats to plan for increases, the expenditures may not appear in the budget for years. Towns that saw the budget challenges begin in 2008 may, in 2011 or 2012, be budgeting for expenditures necessitated as the recession started, now hoping to catch up on necessary repairs, maintenance and upgrades to the infrastructure.

Parks, recreation and tourism: The optional city programs dedicated to parks, recreation and tourism got hit the hardest, decreasing by 3.1 percent in the time period of 2008-2011. It seems cities look first toward optional services when they need to cut. Overall, PRT represented a relatively small portion of the budget, 4.6 percent. So a 3.1 percent cut does not represent that much money but for the citizens who use those services, it can mean a lack of everything from little league programs to a lack of senior citizen activities. A January 31, 2010 article by Michael Booth in The Denver Post about budget cuts in nearby Colorado Springs hit home with residents.

The parks department removed trash cans last week, replacing them with signs urging users to pack out their own litter.

Neighbors are encouraged to bring their own lawn mowers to local green spaces, because parks workers will mow them only once every two weeks. If that.

Water cutbacks mean most parks will be dead, brown turf by July; the flower and fertilizer budget is zero.

City recreation centers, indoor and outdoor pools, and a handful of museums will close for good March 31 unless they find private funding to stay open. Buses no longer run on evenings and weekends. The city won’t pay for any street paving, relying instead on a regional authority that can meet only about 10 percent of the need.

…

“How are people supposed to live? We’re not a ‘Mayberry R.F.D.’ anymore,†said Addy Hansen, a criminal justice student who has spoken out about safety cuts. “We’re the second-largest city, and growing, in Colorado. We’re in trouble. We’re in big trouble.â€

Still, the newspaper coverage seemed to have little impact on policy outcomes. The correlation jumped from r=0.00 in 2009-2010 to r=0.10 in 2010-2011 and r=0.39 in 2011-2012. Again, the increases were similar to those in public safety and public works.

Economic development: Of the four coverage areas, public safety, public works, parks, recreation and tourism and economic development, economic development consistently had the lowest correlation. However, in the three-year period of 2008-2011, economic development budgets were the smallest of the areas studied, accounting for less than 3 percent of the overall budget, but they remained the most stable, increasing by 6.29 percent compared to an average increase of 2.71 percent for overall city budgets in the same time period. While economic development saw the largest relative budget increase over a three-year period, there was little relationship between that increase in newspaper coverage indicating that public officials saw value in economic development without corresponding media coverage. Still, coverage of economic development issues was not lacking. For example, back in 2008, Tim Mekeel reported in the Lancaster (Pa.) New Era about a $4 million allocation being used to rejuvenate existing buildings for multi-use, commercial or industrial projects in the county’s boroughs. In 2003, a Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette by Marlene Lucas brought economic development issues home to the farmers. “A promoter of economic development is trying to recruit dairy producers to Iowa, saying the state’s dairy farmers aren’t satisfying the processors in the state.†But dairy farmer Dave Kunde said this would not be beneficial to the state’s economics. “People think it’s a great deal, but they don’t understand the pricing of milk. It’s under a federal order. Other commodities go with the flow of the market,†Kunde said. Headlines like “Northeast Ohio Needs More Jobs, Economic-Development Expert Tells Chamber’†(Baker, 2006) and “Mississippi Business Climate Improves, but Still Needs Strengthening†(Seid, 2004) show that such issues were issues at least some reporters found worth reporting on even if their stories had no impact on policy changes. The correlation between coverage and policy outcomes in economic development increased from r=0.01 in 2009-2010 to r=007 in 2010-2011, approximating the increases in the other variables. However, the correlation remained at r=0.07 in 2011-2012.

In the 2008-2009 budget year and 2009-2010 budget year, no items of significance were found and the effect sizes were very small (ranging from r=0.00 to r=0.06) and did not change much during those two years. The correlations, however, increased in all four coverage areas in 2010-2011 and remained high in 2011-2012, an increase that has no obvious explanation. Of the four items that showed statistical significance, three involved comparing coverage in 2010-2011 with budgets in 2011-2012. However, in 2011-2012, because the coverage cycle had not been complete and some towns had not yet adopted their budgets, 56 of the 143 total towns in the study had incomplete data, 39 percent. Certainly, this renders the results for the final year open to much more scrutiny. The 2011-2012 budgets may be picking up post-recession growth mandated by inflation pressures and population growth. The fourth item, coverage in 2009-2010 for the 2010-2011 budget cycle for pubic works showed that coverage of public works explained 2 percent (p<0.1) of the variance in the policy change, a small effect size to be sure, further substantiating that even with the relationship is significant, coverage has little relation to policy change over the short-term. In addition, this small effect size was significant only at the p<0.1 level, indicating that there might be a one in 10 chance that this result is accidental and not worth reporting.

Five-year Correlations

The lack of correlation over one year did correspond to other research such as that of Wildavsky who said policy change does not occur overnight. Walker (1977) accented this in his research that correlated coverage of the Highway Safety Act over time, showing that it took several years of coverage in both the mass media and technical safety literature before new legislation was passed. Even Kingdon’s Multiple Streams model acknowledges that it takes time and a window of opportunity for policy change to occur.

Correspondingly, examining changes over a five-year period proved some significant results. In that examination (table 8), more relationships showed up indicating that while media coverage might not have a short-term impact there may be a long-term influence on policy change. Despite the media’s propensity to have short-term memories, the media influence on policy makers may not be so short-term. Models such as the Punctuated Equilibrium model of Baumgartner and Jones (1993) might also explain why broad, policy priorities of city and town governments remain unaffected by media coverage. While a one-year analysis might miss the punctuation, the five-year analysis might account for small, cumulative effects and larger punctuations. However, it was difficult to obtain five consecutive years of budgets for towns, reflecting the decline in the number of towns analyzed. Further, analyzing the data over a five-year period introduces more likelihood that the policy changes may have resulted in the media coverage and public opinion changes rather than policy changes being the result of media coverage and subsequent public opinion in change. While the literature to date indicate that, at least initially, the agendas of the bureaucrats and politicians are set, at least in part, by media coverage, it is certainly possible, as the time period of the study increases, that policies result from other sources than the media and that media coverage follows, rather than precedes, policy change.

| Table 8: Newspaper Terms Correlated with Town Budget | |||

| Â | 2004-2009 Correlation (r) | 2005-2010 Correlation (r) | 2006-2011 Correlation (r) |

| Public safety | 0.08 | 0.14* | 0.01 |

| Public works | 0.11 | 0.25** | 0.22*** |

| Parks, recreation and tourism | 0.09 | 0.41*** | 0.31*** |

| Economic development | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Total | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Â | n=46 | n=75 | n=93 |

|

*Correlation is significant at the 0.10 level (2-tailed) |

|||

The relationship between coverage of public works and policy outcomes was significant in two of the three years studied possibly for similar reasons discussed earlier. Public works just is not as sexy as other areas; in terms of media coverage, it makes headlines when things go wrong, not when they are going right. Coverage of sewage treatment, road construction, water purification, trash collection and construction rarely gets the play of coverage regarding police, fire, EMS, crime (the public safety terms). However, in this simple model, public works reporting, at most, accounted for 6.25 percent of the variation in public works budgeting, a small, or as Hopkins (2002) might say, “minor,†effect size to be sure. In the five-year period from 2004 to 2009, the correlation (r=0.11) was small and insignificant. However, in the two other periods analyzed, 2005-2010 and 2006-2011, the results were still small (r=0.25 and r=0.22 respectively) but were significant.

At the local, citizens have regular involvement with parks, recreation and tourism in everything from softball leagues to walking trails perhaps explaining why coverage of parks, recreation and tourism hits home with administrators and politicians. As an editorial in the May 23, 2006 Macon (Ga.) Telegraph said, “Recreation is not just a ‘quality of life’ issue.†Or as an article in the Dec. 12, 2009 Tulsa (Ok.) World reported, “The public is certain to feel the continued squeeze on the Park and Recreation Department, which has been a frequent target of past budget reductions, Director Lucy Dolman said. ‘We always say it’s bad, but this time it will be devastating,’ she said, adding that it could mean more than 15 layoffs and community center closures’ †(Barber, 2009). The reporting on parks, recreation and tourism over a five-year period accounted for 16.1 percent of the variance in the budget, still moderate according to Hopkins’ classification but still significant, and consistent over two five-year periods. In the first time period studies, like in public works, the correlation was weak (r=0.09) and insignificant. In the two subsequent periods, the results were moderate (r=0.41 and r=0.31) and significant at the highest levels, p<0.01. The relatively large jump between the first five-year period studied and the second was even larger than the jump in public works.

That public safety and economic development were not significant in either five-year model was surprising and seems to indicate that other factors play a more important role in budget changes regarding public safety than the media. In a post 9/11 era, it could be that public safety budget changes have more to do with the national discussion regarding public safety than anything that is said at the local level. Few citizens have any interaction with economic development activities of the city or town, including taxation efforts that are often very long-term and difficult to cover in mass media outlets. In the first time period studied, both public safety and economic development started out trivial, r=0.08 and r=0.07 respectively. Like other variables, the correlation jumped in the second time period but remained low, r=0.14 and r=0.11. The public safety correlation was significant, but only at the 0.10 level.

In all cases, the relationship between total budget change and coverage in the preceding year was trivial and insignificant.

Other Variables

Three other variables provided some insight into the local newspaper media used in this study. The first, ownership, reflected national trends. While consumers tend to trust entities that are locally based more than those that are nationally based (Sinclair and Löfstedt, 2001), the vast majority of media are not locally owned (Bagdikian, 2004). In this study, 31 percent of the 143 papers studied (appendix c) were locally owned, about 10 percent more than the 23.4 percent of independent newspapers Eli Noam found in his 2009 research yet down significantly from the 68.2 percent of independent newspapers in 1960 (Noam, 2009). According to the PEW Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism (2011), Gannett, MediaNews Group, News Corporation, McClatchy and the Tribune Company are the top owners by circulation. However, five companies, GateHouse Media, Community Newspaper Holdings, Gannett, MediaNews Group and Lee Enterprises, own 43 percent of the daily newspapers that sell at least 100,000 print papers on an average weekday. While revenue figures were not available for most of the privately held companies, Gannett’s newspaper division alone brought in $5.44 billion in 2010 and $5.61 billion (Pew Research Center, 2011). As stated earlier, the relationship between local ownership and circulation was significant, yet small with local ownership accounting for some 2 percent of the variance in circulation (r=0.18*).

The second variable of interest, online use, showed that the vast majority of newspapers in the study (73 percent) not only have a website that is updated at least daily, but also make use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter to distribute their news. An additional 16 percent have a website that is updated at least daily but do not make regular use of social media. This reflects national trends as online readership increased nearly 60 percent 2004 and 2009 and continues to go up (Newspaper Association of America, 2011). “In 2010, digital was the only media sector seeing growth. In December 2010, 41 percent of Americans cited the internet as the place where they got most of their news about national and international issues, up 17 percent from a year earlier.†Indeed, as the report showed, “Fully 46 percent of people now say they get news online at least three times a week, surpassing newspapers (40 percent) for the first time†(Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, 2011). The impact online media have on local coverage, local (and hyperlocal) public opinion and local policy changes are trends worthy of much more exploration.

While this study specifically examines the print edition of newspapers as uploaded to either the newspaper’s own website or the EBSCO database, in the last few years, readers have been consuming newspapers in another manner: using mobile devices. As the Newspaper Association of America (Sadowski, 2011) reported, “Many newspapers reported triple-digit page view increases to their mobile sites and apps, demonstrating that newspaper content remains a leading choice for consumers across their multiplatform offerings. … Unique visitor count increases ranged as high as 200 percent, with an average increase of about 70 percent for the publishers reporting.†Studies by the digital audience measurement firm comScore’s Digital Omnivore and Pew Research/Economist Group supported the Newspaper Association of America’s conclusions. Both groups released studies in October of 2011 showing app users went directly to news organization sites to get news instead of going through a search engine or news aggregator. “In August 2011, 7.7 percent of total traffic going to Newspaper sites came from mobile devices – 3.3-percentage points higher than the amount of mobile traffic going to the total Internet. As consumers continue to seek out breaking news and updated information on the go, it is likely that this share of traffic could grow further for non-computer sources†(comScore, 2011). While public opinion can be swayed by consumption of news media online as well as in print, this type of consumption is not at all reflected in the circulation numbers of this study.

The final variable of interest, staff size, also reflected recent national trends. Employment of full-time professional editorial staff peaked in 2000. It then fell 26.4 percent through 2009 according to the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism (2011). The American Society of Newspaper Editors reported in 2010 that American daily newspapers lost another 5,200 jobs in 2009 bringing the total loss of journalists since 2007 to 13,500. Since 2001, ASNE reported, American newsrooms have lost more than 25 percent of their full-time staffers bringing the total of full-time journalists working in daily newsrooms to 41,500, a level not seen since the mid-1970’s. The staff size of newspapers in this study declined 41 percent from 2000-2010 and 21 percent between 2005 and 2010. Overall, according to the American Society of Newspaper Editors (2011), “American newspapers showed a very slim increase in newsroom employees last year, finally halting a three-year exodus of journalists.… The number of professional journalists rose from an estimated 41,500 in 2009 to 41,600 in 2010, according to ASNE’s most recently completed census of online and traditional newspapers. American daily newspapers lost 13,500 newsroom jobs from 2007 to 2010.†The staff size of the papers used in this study decreased 10 percent between 2009 and 2010 and was, obviously, strongly correlated with the circulation of the paper (r=0.70**) supporting data available from other sources.

INTRODUCTION | LITERATURE REVIEW | METHODOLOGY | INITIAL FINDINGS

EXPANDING THE MODEL | CONCLUSIONS | REFERENCES | PDF VERSION

Â