Sept. 11 changed photojournalism too

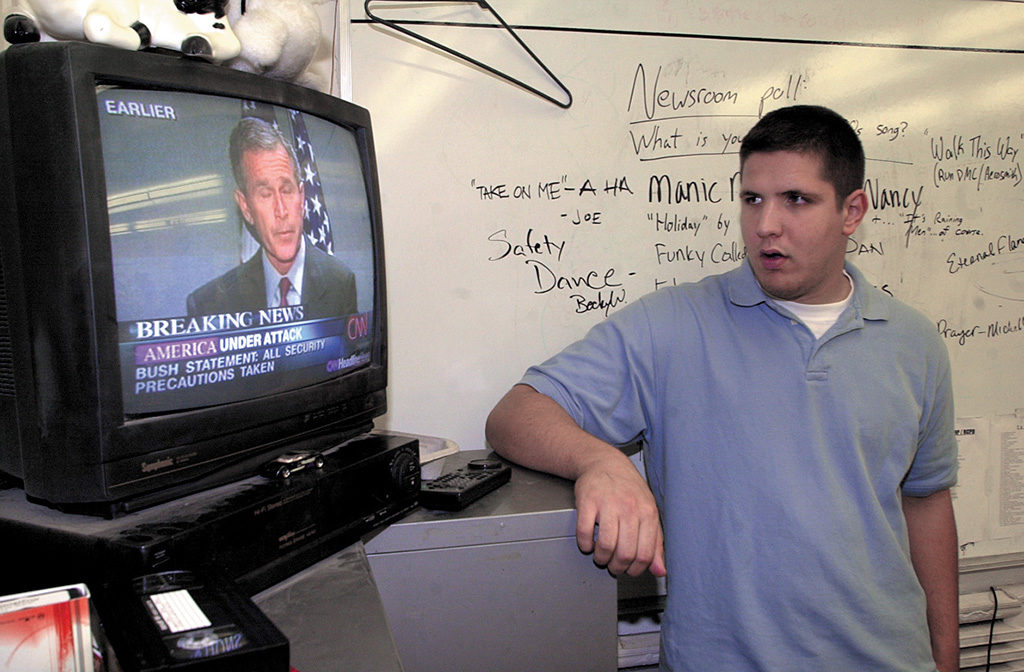

Photo by Carmen Taylor/AP

As we approach the 10th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, everyone is taking some time for reflection. Towns are honoring their first responders. Survivors, family members and friends of those killed and thousands of others are visiting the new memorials around the country. And journalists too are spending time reflecting.

For 9/11 was one of those moments that served as a reminder the power and the importance of quality, timely journalism in a time before Facebook, before Twitter and before Flickr.

As a photojournalist, in my lifetime, I can think of two other events that have made photojournalists stop in their tracks and think about the impact of their work — the very public suicide of Pennsylvania State Treasurer Bud Dywer in 1987 and the Oklahoma City bombing.

I was in Manhattan on Sept. 11. Not New York City. Kansas. And of course the photojournalism students — some of the most talented photojournalists I’ve ever worked with — scrambled to cover the local angles of the attacks. Over the next few days we spent a considerable amount of time discussing the impact of some of the images. It was one of the most documented few hours in American history, no doubt.

I was in Manhattan on Sept. 11. Not New York City. Kansas. And of course the photojournalism students — some of the most talented photojournalists I’ve ever worked with — scrambled to cover the local angles of the attacks. Over the next few days we spent a considerable amount of time discussing the impact of some of the images. It was one of the most documented few hours in American history, no doubt.

I remember walking into the JEA office and hearing that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. I left to go over to the college newspaper newsroom to see how I could help. Watching live news coverage of the second plane hitting the tower and the billowing black smoke, we knew our lives had changed. As journalists, everyone got to work. Photojournalists went over to the local military base where folks were already on high alert. They went to the student union to capture the campus reaction. They went out into the community.

While they, and dozens of reporters, were out in the field, we watched from Kedzie Hall on television as events unfolded. We knew our lives had changed forever. Just as we were in the newsroom, the hallways and our classrooms that day and the days immediately after, editors, designers and photojournalists were having heated discussions about what photos to should have been published as they struggled to document a new, unexpected war on the homefront.

Like this image by Gulnara Samoilova/AP, the haunting photos, in black-and-white, that looked like something out of a movie scene and the aftermath of a nuclear we documented the terror of the people in New York City.

And we all cheered at Thomas E. Franklin’s photo published in the The Bergen Record of firefighters raising the flag at Ground Zero.

And we all cheered at Thomas E. Franklin’s photo published in the The Bergen Record of firefighters raising the flag at Ground Zero.

Images of jumpers resonate

Then we watched the photos the wire services were transmitting, photos of a building in flames, the buildings collapsing, the aftermath at the Pentagon and in Pennsylvania. And we watched in horror as publications and wire services began releasing photos of people jumping or falling from the top floors of the World Trade Center. In real time, live on television and the Web, people were dying. Not just one convicted criminal committing suicide or one baby, dozens or hundreds people in their final moments.

As Dennis Cauchon and Martha Moore wrote in their USA Today article, “The story of the victims who jumped to their deaths is the most sensitive aspect of the Sept. 11 tragedy. Photographs of people falling to their deaths shocked the nation. Most newspapers and magazines ran only one or two photos, then published no more. USA Today ran one photo Nov. 16.

“Still, the images resonate. Many who survived or witnessed the attack say the sight of victims jumping is their most haunting memory of that day.”

Richard Drew‘s photo now entitled “The Falling Man” became iconic in this genre. Five years after the attacks, The Falling Man was identified as Jonathan Briley, a 43-year-old employee of the Windows on the World restaurant.

It was as controversial as the images of Bud Dwyer. Or the baby after the Oklahoma City bombing. It, and simliar images, promoted discussions in newsrooms from San Jose, where the Mercury News ran a nearly full-page photo of the jumpers, to West Palm Beach, Fla. where the Palm Beach Post ran “The Falling Man” as part of a photo page, to page A7 of the New York Times. These photos not only should have been published, they MUST have been published, and any criticism of their publication is unwarranted. This was part of the story, a dreadful part to be sure, but a part of the human experience that made events like 9/11 something to avoid.

As Howell Raines said, while they were concerned for the family, that man “seemed to perfectly capture the tragedy of the day. That man in a sense was all of New York that day.â€

It was a continuation of the ongoing discussion about whether or not to publish such controversial images. But these images and the thousands and thousands of others, including the thousands submitted to the ongoing exhibit Here is New York: A Democracy of Photographs, something that started as a spontaneous outlet for anyone with a camera and became an exhibit of professional and amateur photographs from the World Trade Center disaster, help us realize the true horror of that day in New York City, Washington, D.C. and Stonycreek Township, Penn.

Like the photos that take us to other worlds, to other countries and to other places and times that we could never visit ourselves, the photos from 9/11 help us remember, not only remember what happened that beautiful fall morning, but remember the freedoms that we need to fight for. We should never take those freedoms for granted.

Sometimes journalists doubt the power they have as gatekeepers and as the people who tell us the stories we need and want to hear. The anniversary of Sept. 11, 2011 should also be a reminder of the power of the visual image and how these images, words, videos and audio brought people from all over the world together to watch events unfold. They brought, for a few fleeting second sometimes, the lives of the people experiencing those events onto our computers and into our family rooms and helped us share the experience. As horrifying as it was, thanks to the photojournalists, reporters, designers and editors, it is true, we will never forget.

How are we different?

So, today as we go about our business documenting the lives of people standing in unemployment lines, government officials bickering over useless legislation, kids playing in the park, a many guilty of killing his daughter and all the other things that we document on a daily basis, we have some perspective. Without the words, the pictures, the audio and the video — whether published on a blog, a website, a printed newspaper, a newsmagazine or the evening news — we would have no idea what’s going on in the world.

Of course the media set the agenda for public opinion. Without the media we wouldn’t have a clue what those businessmen making millions of dollars are doing with our money or what animals the family next door is really keeping inside their house. Indeed, without the media we really wouldn’t know much about what’s going on in the world at all. We certainly wouldn’t have nearly as good of a grasp of what happened on Sept. 11 as we do.

While Sept. 11 helps us keep our daily coverage in perspective, it makes it no less important. Without the media, we would have little to remember. As others have said, “Photojournalism got its job back that day.â€

While Sept. 11 helps us keep our daily coverage in perspective, it makes it no less important. Without the media, we would have little to remember. As others have said, “Photojournalism got its job back that day.â€

It’s all local

The real power that day was in the newsroom at Kansas State where students like Collegian Managing Editor Nick Bratkovic, Editor Bryan Scribner, and photographers like Matt Stamey, Evan Semon, Kelly Glasscock, Mike Shepherd spend the day and night trying to document the world they knew had changed. Their images, even a decade later, remind all of us what it was like to be in Manhattan — Kansas — that day. And they remind us of the power of documentary photojournalism.

MORE THOUGHTS

- Here is New York: A Democracy of Photographs

- Kratzer, Renee Martin. “How Newspapers Decided to Run Disturbing 9/11 Photos.” Newspaper Research Journal. FindArticles.com. 09 Sep, 2011.

- Junod, Tom. “The Falling Man.”

Leave A Comment